|

Monday, June 8, 2020

Weekend Roundup

While this week was unfolding, I've been reading a book by Sarah

Kendzior: Hiding in Plain Sight: The Invention of Donald Trump and

the Erosion of America. She is a journalist based in St. Louis,

with a Ph.D. in anthropology and a specialty in post-Soviet Central

Asia and its descent into mafia capitalism and oligarchy. She sees

Trump as part of a vast criminal enterprise, anchored in Russia,

which she insists on describing as "hostile to America." I think

she has that analysis ass-backwards. Capitalism's driving force

everywhere is greed, which constantly pushes the limits of custom

and law. The only thing that separates capitalists from criminals

is a democratic state that regulates business and enforces limits

on destructive greed. The former Soviet Union failed to do that,

but the United States has a checkered history as well, with the

major entrepreneurs of the 19th century known as Robber Barons,

and a sustained conservative assault on the regulatory state at

least since 1980. Trump may be closer to the Russian oligarchs

than most American capitalists because of his constant need to

raise capital abroad, but he is hardly Putin's stooge. Rather,

they share a common desire to suppress democratic regulation of

capital everywhere, as well as an itch for suppressing dissent.

Arguing that the latter is anti-American (treason even) ignores

the fact that that's a big part of the program of the reigning

political party in the US.

Kendzior's arguments in this regard annoy me so much I could go

on, explaining why the supposed US-Russia rivalry is based on false

assumptions, and why Democrats are hurting themselves by obsessing

on the Trump/Russia connection. I was, after all, tempted at several

points to give up on the book. But I stuck with it: it's short, and

anyone who despises Trump that much is bound to have some points.

Also, I lived in St. Louis a few years myself, so was curious what

she had to say about her battleground state. My interest paid off

with her discussion of the 2014 protests against police brutality

in Ferguson, a majority-black suburb just north of St. Louis with

a predominantly white police force that was largely self-funded by

arrests and fines. This is history, but it's also today in microcosm

(pp. 164-166):

Understanding Ferguson is not only a product of principle but of

proximity. The narrative changes depending on where you live, what

media you consume, who you talk to, and who you believe. In St. Louis,

we still live in the Ferguson aftermath. There is no real beginning,

because [Michael] Brown's death is part of a continuum of criminal

impunity by the police toward St. Louis black residents. There is no

real end, because there are always new victims to mourn. In St. Louis,

there is no justice, only sequels.

Outside of St. Louis, Ferguson is shorthand for violence and

dysfunction. When I go to foreign countries that do not know what

St. Louis is, I sometimes joke, darkly, that I'm from a "suburb of

Ferguson." People respond like they are meting a witness of a war

zone, because that is what they saw on TV and on the internet. What

they missed is that Ferguson was the longest sustained civil rights

protest since the 1960s. The protest was fought on principle because

in St. Louis County, law had long ago divorced itself from justice,

and when lawmakers abandon justice, principle is all that remains. The

criminal impunity many Americans are only discovering now -- through

the Trump administration -- had always structured the system for black

residents of St. Louis County, who had learned to expect a rigged and

brutal system but refused to accept it.

In the beginning, there was hope that police would restrain

themselves because of the volume of witnesses. But there was no

incentive for them to do so: no punishment locally, and no

repercussions nationally. Militarized police aggression happened

nearly every night, transforming an already traumatic situation into a

showcase of abuse. The police routinely used tear gas and rubber

bullets. They arrested local officials, clergy, and journalists for

things like stepping off the sidewalk. They did not care who witnessed

their behavior, even though they knew the world was

watching. Livestream videographers filmed the chaos minute by minute

for an audience of millions. #Ferguson, the hashtag, was born, and the

Twitter followings of those covering the chaos rose into the tens of

thousands. But the documentation did not stop the brutality. Instead,

clips were used by opponents of the protesters to try to create an

impression of constant "riots" that in reality did not occur. The

vandalism and arson shown on cable news in an endless loop were

limited to a few nights and took place on only a few streets.

National media had pounced on St. Louis, parachuting in when a

camera-ready crisis was rumored to be impending, leaving when the

protests were peaceful and tame. Some TV crews did not bother to hide

their glee at the prospect of what I heard one deem a real-life Hunger

Games, among other flippant and cruel comments. The original protests,

which were focused on the particularities of the abusive St. Louis

system, became buried by out-of-town journalists who found out-of-town

activists and portrayed them as local leaders. The intent was not

necessarily malicious, but the lack of familiarity with the region led

to disorienting and insulting coverage. Tabloid hype began to

overshadow the tragedy. Spectators arrived from so many points of

origins that the St. Louis Arch felt like a magnet pulling in fringe

groups from around the country: Anonymous and the Oath Keepers and the

Nation of Islam and the Ku Klux Klan and the Revolutionary Communist

Party and celebrities who claimed they were out of deep concern and

not to get on television. Almost none of the celebrities ever

returned.

In fall 2014, the world saw chaos and violence, but St. Louis saw

grief. Ask a stranger in those days how they were doing and their

eyes, already red from late nights glued to the TV or internet, would

well up with tears. Some grieved stability, others grieved community,

others simply grieved the loss of a teenage boy, unique and complex as

any other, to a system that designated him a menace on sight. But it

was hard to find someone who was not grieving something, even if it

was a peace born of ignorance. It was a loss that was hard to convey

to people living outside of the region. I covered the Ferguson

protests as a journalist, but I lived it as a St. Louisan. Those are

two different things. It is one thing to watch a region implode on

TV. It is another to live within the slow-motion implosion. When I

would share what I witnessed, people kept urging me to call my

representative, and I would explain: "But they gassed my

representative too."

By the way, here are the latest section heads (as of 7:37 PM CDT

Sunday) in The New York Times'

Live Updates on George Floyd Protests:

- Majority of the Minneapolis City Council pledges to dismantle the

Police Department

- Trump sends National Guard troops home

- New York's mayor pledges to cut police funding and spend more on

social services

- Democratic lawmakers push for accountability, but shy away from

calls to defund the police

- Barr says he sees no systemic racism in law enforcement

- Romney joins protesters in Washington.

- Protesters march through Manhattan, calling for an end to police

violence.

- Thousands turn out in Spokane, Wa., to protest "a virus that's

been going on for 400 years."

- Biden will meet with the family of George Floyd in Houston.

- The view from above: aerial images of protests across the

country.

[link]

- A Confederate status is pulled down during a protest in Virginia

- Global protests against racism gain momentum.

- An officer shot an anti-bias expert who was trying to end a clash

at a protest in San Jose, Calif.

A couple items there look like major breaks with the past. While

the "progressive" mayors of Minneapolis and New York seems to have

spent much of the last week being intimidated by the police forces

that supposedly work for them, the balance of political forces in

both cities may have shifted to viewing the police as the problem,

not the solution. I started off being pretty skeptical of the

protests, and indeed haven't been tempted to join them. But it

does appear that they're making remarkable progress. And while I

abhor any violence associated with the protests, one should never

allow such noise to distract from the core issue of the protests.

Indeed, given that so much of the violence the media likes to

dwell on is directly caused by the police and the government's

other paramilitary forces, it's hard not to see that the only

way this ever gets resolved is by restoring trust and justice --

which is to say, by radically reforming how policing is done in

America.

I expected such sprawl at the start of the week that I decided not

to bother organizing sublists. Still, some fell out during the process,

but I haven't gone back and organized as many as might make sense.

In particular, there are several scattered pieces on the "jobs

report": the one by Robert J Shapiro is the most important, but I

got to it after several others.

This wound up running a day late. Only a couple links below came

out on Monday, and I tried to only pick ones that added to stories

I already had (e.g., I added Yglesias' piece on economic reporting,

but didn't pick up the one on Biden's polling).

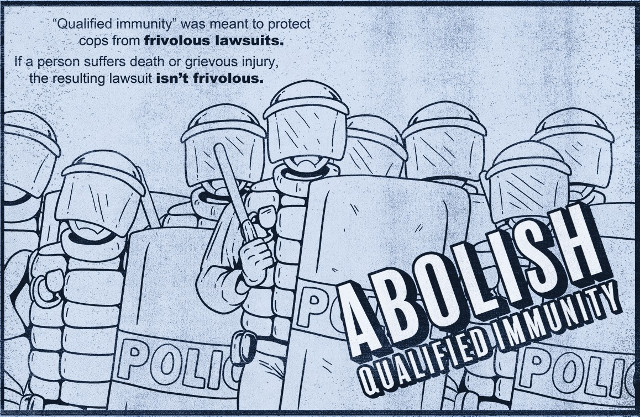

Here's a piece of artwork from

Ram Lama Hull occasioned

by the recent demonstrations. I pulled this particular one (out of

many) from his

Facebook page.

Some are also on

Imgur.

Here's a piece of artwork from

Ram Lama Hull occasioned

by the recent demonstrations. I pulled this particular one (out of

many) from his

Facebook page.

Some are also on

Imgur.

Qualified immunity is a legal doctrine that has come up a lot

recently, as it makes it very difficult to hold police officers

liable for their acts, even the use of excessive or deadly force.

For example:

Parting tweet (from Angela Belcamino):

Who else but Trump could bring back the 1918 pandemic, the 1929 Great

Depression, and the 1968 race riots all in one year?

Some scattered links this week:

Anne Applebaum:

History will judge the complicit: "Why have Republican leaders

abandoned their principles in support of an immoral and dangerous

president?" Why does she think "Republican leaders" have principles

any different from their president? Applebaum is especially concerned

about Lindsay Graham. I can't find the reference, but have a clear

memory of Graham, when he was in the House in the 1990s, explaining

that Republicans have to secure as many long-term posts of power as

possible, before demographic changes make it impossible for R's to

win fair elections. So he was always a practical, anti-democratic

schemer. Back in 2016, Trump may have offended his sense of what's

possible, but by winning he sealed his case, and won Graham over.

Applebaum asks, "what would it take for Republican leaders to admit

to themselves that Trump's loyalty cult is destroying the country

they claim to love?" The answer is catastrophic defeat at the polls,

so bad it sweeps all of them out of office. Losing the Senate seats

of Graham and McConnell in 2020 would be a good start. David Atkins/Dante Atkins:

Trump thought brutalizing protesters would save him. He was wrong.

"His gamble on creating a militarized culture war has done the opposite

of what he hoped for."

Even before the brutal killing of George Floyd by officers of the

Minneapolis Police Department, Trump knew that he would need to

maximize his culture war appeal to non-college whites to make up

ground lost to the faltering economy. There can be little doubt

that Trump saw opportunity in the protests that followed to dust

off the Nixon playbook, vowing to restore "law and order" in a

country furious that the law seemed to protect only some, while

enforcing a brutal order on others. If Trump's actions threatened

to turn the culture war into an active shooting war, that would

just be collateral damage on the road to his political recovery.

The Trump orbit considers the iconography of jingoistic militarism

and the violent suppression of protest to be a political winner. . . .

Trump, like Nixon before him, uses "law and order" as a way of "talking

about race without talking about race." In this narrative, a president

who supports American "traditional culture" and stands strong against

people who agitate for racial justice will win over a "silent majority"

of people who just don't want to be disturbed and want to have some

peace and quiet from their politics. . . .

In one sense, [Trump]'s right: people are exhausted with chaos, and

they do want a respect for law and order. The problem for Trump? The

chaos is in large part of his own making, and insofar as it isn't,

he's in the way of solving the problems created by institutional

racism and overlapping hierarchies of oppression. The massive wave

of police brutality has woken even many previously disengaged white

people up to the need for true equality under the law, and an order

in which everyone, including police and the president, are held to

account. And many of the same people Trump is trying to persuade now

believe that kicking him out of the White House is a necessary

prerequisite for making that vision a reality.

Dean Baker:

The jobs report was good, but the economy is still bad. But see

Shapiro, below. Peter Baker/Maggie Haberman/Katie Rogers/Zolan Kanno-Youngs/Katie

Benner:

How Trump's idea for a photo op led to havoc in a park. Kevin Baron:

Trump finally gets the war he wanted. Katelyn Burns:

John Cassidy:

Trump represents a bigger threat than ever to US democracy. Sean Collins:

Tray Connor/Lisa Khoury:

Every Buffalo cop in elite unit quits to back officers who shoved

elderly man to ground. Two officers were suspended for attacking

a 75-year-old protester, cracking his head against the ground and

leaving him bleeding. Fifty-seven quit to protest the suspensions. Mark Danner:

Moving backward: Hypocrisy and human rights. Derek Davison/Alex Thurston:

Expect more military "liberal interventionism" under a Joe Biden

presidency: My first instinct was to play this down, but the sheer

number of likely foreign policy mandarins mentioned, as well as Biden's

alleged desire to hire anti-Trump Republicans, makes me nervous. One

reason I doubt we'll see more interventionism is that I think the

current generation of military leaders, many burned from Afghanistan

and Iraq (and Syria and Libya), are likely to resist -- especially

pleas on "humanitarian" grounds. Also, as I recall, Biden pushed for

a more minimal policy in Afghanistan under Obama. On the other hand,

his career in Congress always supported the hawks. People do tend

to get more cautious with age, so there's that. But I do agree there

is reason to fret over his personnel decisions. Elizabeth Dwoskin/Nitasha Tiku:

Facebook employees said they were 'caught in an abusive relationship'

with Trump as internal debates raged. Ariel Dorfman:

Trump isn't a dictator. But he has a dictator's sense of impunity.

Rob Eshman:

What the old Jewish radical taught me about George Floyd: Our friend,

Marsha Steinberg. Franklin Foer:

The foundations of the Trump regime are starting to crumble.

Over the course of his presidency, Donald Trump has indulged his

authoritarian instincts -- and now he's meeting the common fate of

autocrats whose people turn against them. What the United States is

witnessing is less like the chaos of 1968, which further divided a

nation, and more like the nonviolent movements that earned broad

societal support in places such as Serbia, Ukraine, and Tunisia,

and swept away the dictatorial likes of Milosevic, Yanukovych,

and Ben Ali.

Matt Ford:

The police were a mistake: "Law enforcement agencies have become the

standing armies that the Founders feared." Masha Gessen:

Donald Trump's fascist performance.

Donald Trump thinks power looks like masked men in combat uniforms lined

up in front of the marble columns of the Lincoln Memorial. He thinks it

looks like Black Hawk helicopters hovering so low over protesters that

they chop off the tops of trees. He thinks it looks like troops using

tear gas to clear a plaza for a photo op. He thinks it looks like him

hoisting a Bible in his raised right hand.

Trump thinks power sounds like this: "Our country always wins. That

is why I am taking immediate Presidential action to stop the violence

and restore security and safety in America . . . dominate the streets . . .

establish an overwhelming law-enforcement presence. . . . If a city or

state refuses . . . I will deploy the United States military and quickly

solve the problem for them. . . . We are putting everybody on warning. . . .

One law and order and that is what it is. One law -- we have one beautiful

law." To Trump, power sounds like the word "dominate," repeated over and

over on a leaked call with governors.

Chip Gibbons:

Donald Trump's "Antifa" hysteria is absurd. But it's also very dangerous.

I have a lot of trouble with "antifa": I'm not sure they exist, but if

they do, I'm pretty sure they aren't part of the left -- which I'd define

as the movement to universalize equal rights, secure peace, and enhance

community through cooperation. Fascists hate the left for just these

reasons, but more often than not they also hate other people, often for

very arbitrary reasons (like race, religion, or favorite football teams).

So it stands to reason that there are people who don't have any particular

commitment to the left but still hate fascists -- because, well, hate

begets more hate. After all, we live in a society that still puts a lot

of stock in violence.

Susan B Glasser:

#Bunkerboy's photo-op war. Constance Grady:

A reading list to understand police brutality in America. Garrett M Graff:

The story behind Bill Barr's unmarked federal agents. Also see:

Washington DC now controlled by gunmen under William Barr's command, and

William Barr's unaccountable nameless army suppresses dissent and

threatens democracy, which starts off with Chris Murphy tweeting

"We cannot tolerate an American secret police." Alisha Haridasani Gupta:

Why aren't we all talking about Breonna Taylor? Could be that this

particular case is complicated by the "war on drugs," which allowed

police to "serve a no-knock warrant" in the middle of the night, and

guns: she was killed after her boyfriend shot at a suspected intruder,

which turned out to be armed police who returned fire massively and

blindly (or at least that's how I understand it went down). As both

the reason for the break in and the firefight were deliberate choices

made by police, it's hard not to think that this could have been

handled differently, in a way where no one got shot, and it's hard

to dismiss the idea that racism didn't factor into those choices,

even if the police never saw the person they were killing. But doesn't

this also raise a key question about guns? A big part of the common

rationale for owning a gun is the idea that you can use it to defend

your home from invasion -- but clearly that doesn't work in cases

where the police are the invaders. Maybe that rationale isn't as

smart as its advocates think? Sean Illing:

Will he go? "A law professor fears a meltdown this November."

Interview with Lawrence Douglas, who has a book on this: Will He

Go? Trump and the Looming Election Meltdown in 2020. This strikes

me as something not worth worrying about now, although that anyone

can raise such questions reminds us that Trump has no regard for the

Constitution and the rule of law. I can't imagine that anyone in a

position of power would support Trump in spite of a clear electoral

defeat.

Why the policing problem isn't about "a few bad apples": "A former

prosecutor on the fundamental problem with law enforcement: 'The system

was designed this way.'" Interview with Paul Butler, Georgetown law

professor, former federal prosecutor, author of Chokehold: Policing

Black Men. Quinta Jurecic/Benjamin Wittes:

The law-enforcement abuses that don't bother Trump: "The president

believes that those who oppose him should be punished, but that those

who support him should be free to do as they please." Fred Kaplan:

Roge Karma:

Chris Hayes on how police treat black Americans like colonial subjects:

Interview with Hayes, who wrote a very clear book on the subject,

A Colony in a Nation.

We're seeing tactics of policing that are usually used on people that

are outside of view: pressure, harassment, and ultimately domination.

I think the word domination is so remarkable. The president has been

explicit on this: The goal is domination. And what does domination look

like? It looks like a knee on the neck. In fact, a boot to the neck is

like the oldest trope we have to represent domination and represent

tyranny. What is the flag of the colonies? It's a snake that reads,

"Don't tread on me." Do not step on me. Do not place your foot on me.

That is domination. And if you do, I will react.

Annie Karni/Maggie Haberman:

How Trump's demands for a full house in Charlotte derailed a

convention. Amit Katwala:

Sweden's coronavirus experiment has well and truly failed. Philip Kennicott:

The dystopian Lincoln Memorial photo raises a grim question: Will they

protect us, or will they shoot us? Catherine Kim:

Jen Kirby:

The disturbing history of how tear gas became the weapon of choice against

protesters: "The chemical weapon was originally marketed to police as

a way to turn protesters 'into a screaming mob.'" Interview with Anna

Feigenbaum, author of Tear Gas: From the Battlefields of World War I

to the Streets of Today. Ezra Klein:

America at the breaking point: "The social upheaval of the 1960s

meets the political polarization and institutional dysfunction of the

present." I don't have time to write about this piece, but probably

should refer to it at some point when I finally try to sum up what's

going on. I've always hated the notion that the 1960s divided and

broke America. Rather, events exposed hypocrisies and weaknesses,

but rather than heal them, political reaction took over and turned

us into fantasists. That the same fractures have returned -- sure,

plus some new ones -- should remind us that failure to heal can only

be ignored for so long. Elizabeth Kolbert:

How Iceland beat the coronavirus. Paul Krugman:

Donald Trump is no Richard Nixon: "He -- and his party -- is much,

much worse." The subhed is critical, because is less the leader of his

party than the vessel into which fifty years of megalomania and cynicism

has been poured, the creature grown out of such vile soil. The first

comparison I recall between Trump and Nixon concerned their respective

convention acceptance speeches in 1968 and 2016: Nixon's was much more

concise, and much more cunning, a carefully constructed pitch to the

American people that exploited their feelings while betraying little of

Nixon's real ambitions, whereas Trump's was, despite being scripted, an

incoherent mess. Their presidencies have followed from those initial

premises, but they started out from different places, and to my mind

that makes Nixon more culpable for the ensuing disaster. In fact, when

Trump apes Nixon's law-and-order rants, he's not just repeating past

mistakes but testifying to Nixon's continued legacy. So I really don't

have much patience when liberals like Krugman point out that Nixon

put his signature to some pieces of progressive legislation (like the

Clean Air Act) that Trump has sought to trash. Nixon was smart enough

to bend with the wind, but he was also devious enough to put Donald

Rumsfeld in charge of the Office of Economic Opportunity, and subvert

LBJ's "Great Society" programs from the inside.

Trump takes us to the brink: "Will weaponized racism destroy

America?" Heather Long/Andrew Van Dam:

The black-white economic divide is as wide as it was in 1968: "14

charts show how deep the economic gap is and how little it has changed

in decades. The covid-19 recession is also hitting black families and

business owners far harder than whites." German Lopez:

How violent protests against police brutality in the '60s and '90s

changed public opinion: "The backlash to unrest in the '60s gave

the country Richard Nixon, one study found. But we don't know if that

will apply today." One thing not noted here is that we tend to conflate

two different things when we remember "violence in the '60s": "race

riots" which flared up in various cities from 1965-68, most often in

response to local police acts; and the police riot against anti-war

demonstrators at the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago. Neither

of these should be framed as "protests against police brutality" --

sure, they were occasioned by and exemplified by police brutality,

but they weren't organized as protests. I've long felt that the

former were pent-up explosions of anger, a release of pressures

that had built up over decades of racism and impoverishment, as

I noted that it was very rare for any city to "riot" more than

once. Repeated experiences were prevented not by police dominance

but by community leaders organizing bases of political power.

(Also helpful were cases where white political leaders responded

by getting out into the streets and making their concerns visible,

as John Lindsay did in New York. RFK, campaigning in Indianapolis

when Martin Luther King was killed, was also effective as keeping

anger from turning into riot.) It is true that Nixon cultivated

a backlash against blacks and anti-war protesters, but one thing

that helped him was that he was out of office when the "violence"

happened, unlike Trump. Of course, Nixon was responsible for much

of the violence after he became president in 1969 -- in America,

and much, much more around the world.

How to reform American police, according to experts.

- Police need to apologize for centuries of abuse

- Police should be trained to address their racial biases

- Police should avoid situations that lead them to use force

- Officers must be held accountable in a very transparent way

- On-the-job incentives for police officers need to change

- We need higher standards -- and better pay -- for police

- Police need to focus on the few people in communities causing chaos and violence

- We need better data to evaluate police and crime

Kate Maltby:

Viktor Orbán's masterplan to make Hungary greater again. Peter Manseau:

The Christian martyrdom movement ascends to the White House: "A

former professor of Kayleigh McEnany, Trump's new press secretary,

explores her enduring obsession with religious persecution and death." Branko Marcetic:

American authoritarianism runs deeper than Trump. Josh Marshall:

Dylan Matthews:

How today's protests compare to 1968, explained by a historian.

Interview with Heather Ann Thompson, author of Blood in the Water:

The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy. Ian Millhiser:

Terry Nguyen:

There isn't a simple story about looting. Tim Noah:

Donald Trump is celebrating the wrong economic accomplishment: "The

president wants credit for a largely illusory blip of improvement in the

job market. He should be going all-in on the $600 sweeteners." Anna North/Catherine Kim:

These videos show the police aren't neutral. They're counterprotesters.

Osita Nwanevu:

Tom Cotton and the elite media's dalliance with illiberalism. The

New York Times published an op-ed by the Arkansas Republican called

Send in the troops, demanding that the US military "restore order" --

a task that same military has repeatedly failed to do in Afghanistan

and Iraq (indeed, a sober analysis would recognize that the US military

only made those situations worse, and not for lack of arms or brutality).

The Times justified printing Cotton with its commitment to airing "all"

voices (meaning conservative ones)

Alice Miranda Ollstein/Dan Goldberg:

Mass arrests jeopardizing the health of protesters, police. Richard A Oppel Jr/Lazaro Gamio:

Minneapolis police use force against black people at 7 times the rate

of whites. Alex Pareene:

The police take the side of white vigilantes: "Over the past week,

cops have shown that they share a coherent ideology." Daniel Politi:

Linda Qiu:

Trump's false claim that 'nobody has ever done' more for the black

community than he has: "The records of Abraham Lincoln and Lyndon

B Johnson, among others, beg to differ." Assuming pre-Lincoln presidents

are ineligible, I thought it might be easier to list the ones who had

done less (or who had done more harm). Andrew Johnson was more blatantly

racist than practically anyone. And Woodrow Wilson did major harm in

segregating the federal government. But beyond that just makes my head

hurt. David Remnick:

An American uprising: "Who, really, is the agitator here?" Brian Resnick:

Rubber bullets may be "nonlethal," but they can still maim and kill:

"The dangers of 'nonlethal' police weapons -- like rubber bullets,

flash-bangs, and tear gas -- explained." As I recall, Israeli soldiers,

who use a lot of rubber bullets on Palestinians, like to aim for eyes.

The group found 26 studies on the use of rubber bullets around the world,

documenting a total of 1,984 injuries. Fifteen percent of the injuries

resulted in permanent disability; 3 percent resulted in death. When the

injuries were to the eyes, they overwhelmingly (84.2 percent) resulted

in blindness.

David Roberts:

The coronavirus crisis has revealed what Americans need most: Universal

basic services. Interview with Andrew Percy, co-author with Anna

Coote of The Case for Universal Basic Services. Katie Rogers:

Ivanka Trump blames 'cancel culture' after college pulls her commencement

speech: She was scheduled to address graduates of Wichita State

University "Tech." (What is this "Tech"? Looks like the former Wichita

Area Technical College [WATC], which is to say it it's not even the

real third-tier state college in Kansas. I attended WSU for a year

back when my only credential was a GED, and parlayed that into a

scholarship at a much fancier college. WATC was originally an adult

extension of the Wichita East High vocational program.) I'd like to

know more about how this got contracted (and what the kill fee is).

If Ivanka wanted to look for a prestige spot to speak, she settled

pretty low. On the other hand, I can't imagine anyone there thinking

she's just what WSU Tech needed to burnish its image -- unless, of

course, one of the Kochs (who have a lot of pull at WSU) whispered

in their ears. How it got canceled is no mystery. It was such a

patently stupid idea, all it took was for one of the faculty to

circulate a petition, which damn near everyone signed. "Cancel

culture" is another new one for me (although evidently not for

Vox). Controversial figures often get scheduled for events

then canceled, but it's almost never due to a vogue for canceling.

Usually, some hidden power (like the Kochs) stomps on the autonomy

of some student group. Or sometimes, as in this case, a popular

uprising spoils some shady insider deal. For more, see Daniel

Caudill:

WSU Tech reverses course; Ivanka Trump will not be a commencement

speaker. Main additional piece of news here is that WSU Tech

President Sheree Utash "serves on the American Workforce Policy

Advisory board," giving her a connection to Ivanka, probably via

Mike Pompeo (Trump's Secretary of State, formerly US Representative

for Wichita area). Philip Rucker/Ashley Parker/Matt Zapotosky/Josh Dawsey:

With White House effectively a fortress, some see Trump's strength --

but others see weakness. Also by Dawsey, with David Nakamura/Fenit

Nirappil:

'Vicious dogs' versus 'a scared man': Trump's feud with Bowser

escalates amid police brutality protests. Noam Scheiber/Farah Stockman/J David Goodman:

How police unions became such powerful opponents to reform efforts.

Michael Shank:

How police became paramilitaries.

That beat cops so often look like troops is not just a problem of

"optics." There is, in fact, a "positive and statistically significant

relationship between 1033 transfers and fatalities from officer-involved

shootings," according to recent research. In other words, the more

militarized we allow law enforcement agents to become, the more likely

officers are to use lethal violence against citizens: civilian deaths

have been found to increase by about 130 percent when police forces

acquire significantly more military equipment. . . .

Law enforcement has, in fact, been training for a moment like this --

specifically by learning techniques and tactics from Israeli military

services. As Amnesty International has documented, law enforcement

officials from as far afield as Florida, New Jersey, Pennsylvania,

California, Arizona, Connecticut, New York, Maryland, Massachusetts,

North Carolina, Georgia, Washington state, and the D.C. Capitol have

traveled to Israel for such training. These programs, according to

research backed by Jewish Voice for Peace, focus on exchanging methods

of "mass surveillance, racial profiling, and suppression of protest

and dissent."

Robert J Shapiro:

No, the unemployment rate didn't really drop in May: "Donald Trump

bragged about a bogus jobs number and defiled George Floyd's name in

the process." This strongly suggests that the BLS cooked the books to

give Trump a number (13.3% unemployment) he could brag about. This did

this by not counting 9 million people who weren't working but could be

construed as still having jobs (e.g., unpaid furloughed workers). The

true number is closer to 19.0%. Rebecca Solnit:

As the George Floyd protests continue, let's be clear where the violence

is coming from: "Using damage to property as cover, US police have

meted out shocking, indiscriminate brutality in the wake of the

uprising." Jeffrey St Clair:

Roaming charges: Mad bull, lost its way: I don't particularly like

him, and rarely read him, but some weeks deserve one of his laundry

lists, and he notices somethings that few other people do. For instance,

he dug up a headline from 2003: "Rumsfeld: Looting is transition to

freedom," adding: "Perhaps Rumsfeld will write an amicus brief on

behalf of the more than 10,000 protesters arrested for rioting,

looting and just pissing off cops." Yeganeh Torbati:

New Trump appointee to foreign aid agency has denounced liberal democracy

and 'our homo-empire': Meet "Merritt Corrigan, USAID's new deputy

White House liaison." Emily VanDerWerff:

America's contradictions are breaking wide open: "On Donald Trump,

standing outside a church, pretending to be strong." Vox's TV critic,

but isn't it all TV these days? Alex Ward:

Adam Weinstein:

This is fascism: "Trump is sending an unambiguous message to a country

in turmoil -- and his armed supporters, from cops to vigilantes, hear it

loud and clear." Philip Weiss:

Jordan Weissmann:

Here's what happens if Republicans let those $600 unemployment benefits

expire. Robin Wright:

Is American becoming a banana republic? Matthew Yglesias:

Gary Younge:

What Black America means to Europe. The size of the protests has

surprised me everywhere, but especially in Europe. Still, as a placard

in a photo here says, "The UK is not innocent."

George Floyd's killing comes at a moment when America's standing has

never been lower in Europe. With his bigotry, misogyny, xenophobia,

ignorance, vanity, venality, bullishness, and bluster, Donald Trump

epitomizes everything most Europeans loathe about the worst aspects

of American power. . . . Although police killings are a constant, gruesome feature of

American life, to many Europeans this particular murder stands as

confirmation of the injustices of this broader political period.

It illustrates a resurgence of white, nativist violence blessed

with the power of the state and emboldened from the highest office.

It exemplifies a democracy in crisis, with security forces running

amok and terrorizing their own citizens. The killing of George

Floyd stands not just as a murder but as a metaphor.

Li Zhou:

Ask a question, or send a comment.

|